There are benchmarks and there are standards, but there is no constant when it comes to objectivity in journalism. Every story has unique facets which can change from day to day, the media emphasis shifting, voices promoted or silenced as events progress and situations change. In most cases it is appropriate to sit back and let those involved do the talking, and it is for the audience to be aware of the selection of voices, or the lack of access to key players.

Reporting on escalating civil conflict across the globe, Western media often seems blinkered to the idiosyncracies and pushes for the United Nations to arbitrate in order to quell the violence and pacify the region. The rise of user-generated content reinforces this standpoint; the atrocities we see in the news are despicable, but is outcry and pressure enough to elicit the right solution when more human lives are at stake?

If diplomacy fails, the UN have limited powers of arbitration beyond arming one group or bombing another, and media influence upon such decisions will always come from an unbiased standpoint. Media backing is unequivocal when Western powers paint themselves as the saviours of undemocratic, un-Christian societies. Conflict cannot be stopped by adding munitions any more than fire can be extinguished with petrol, therefore it could be said that unsophisticated media interpretation of events, and it’s subsequent influence, can do more harm than good.

Intervention is a double-edged sword: In Syria unarmed citizens are being bombed out of their homes, although their convictions remain intact. Would supplying them with weapons create a level playing field? Are the Syrian people magicians who can shoot rockets from the sky?

There is no instant defence against attack from above, in fact the intensification of shelling from Assad’s army may well be justified by ‘strengthening’ the peoples movement. Perhaps in the future an alternative recourse from failed diplomacy, sanctions, and militarisation maybe identified.

Some may argue that arming Libya was a success that halted the domination of an oppressive regime, but in the absence of power the people of Libya have not embraced the gift of democracy with enthusiasm. The situation remains one of a divided populous, only now there are more weapons, more danger.

Factor in that which makes the state of Libya a viable location for intervention (militarily strategic Middle Eastern geography; oil-rich, iconic figurehead dictator to topple) and the smoke clears; intervention is not just about conflict prevention, it is about the interests of the most powerful nations.

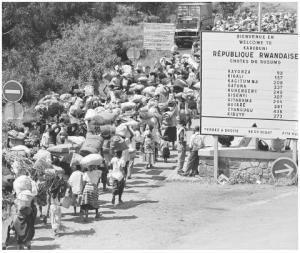

The reticence of major powers to green light intervention in African civil conflicts is symptomatic of three main themes: Poor relationships with governments, lack of perceived gain, and fear of criticism. The ineffective UN peacekeeping presence in Rwanda during the 90s painted an image of an armed force in flux, studying the situation in order to understand how best to proceed without contravening international mandates. All the while genocide continued around them.

Governments with no transparency make it nigh on impossible for the media to unearth the truth; there is also a significant risk element in genocidal tribal conflict such as that in Rwanda.

Kofi Annan, UN special envoy to Syria, this week vocalised his standpoint on affecting the outcome of the government rebel conflict- he denounced the use of force and weapons by UN forces, stating it was out of the question. If diplomacy makes no progress, what will be the UN’s next resort? Sanctions against Syria would harm an already beleaguered resistance, but does the UN have another viable alternative?

Media clamour will add weight to the discourse of armed intervention, although in doing so any claims to objective reporting will be null and void.