By way of a disclaimer, no hyperlinks in this article go directly to any potentially offensive websites. The site I used for research, http://www.gotwarporn.com, has since gone down.

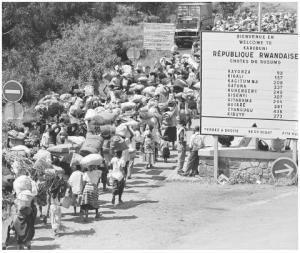

The culture of the Western world is in flux, defined by an indistinct, insignificant year on a meaningless timeline. Since the Second World War the U.S. have been exporting their culture across the world, offering democracy with one hand, a pointing a gun with the other. In return the rest of the globe can expect to concede exclusivity of their identity, their resources and their politics; they can expect their culture and traditions to be undermined or lost; their people divided by changing values to the extreme where they turn upon one another. Neo-imperialism threatens any nation state under the premise of protectionism, resource war or ideological difference.

Consumer culture in the West holds up a cracked mirror to its distorted values and manufactures to normalise. Computer games don’t beget violence, quite the opposite in fact, they exist as an outlet to the violence which is no longer seeping through the cracks of society, but growing like fungus on the walls. Some seek to sanitise this outlet for aggression which is akin to war censorship; violence is a part of our humanity and if we seek to suppress it, it will merely foment elsewhere. The technological advances in entertainment are matched by the technologies of the battlefield; soldiers are all equipped with cameras, on the sights of their rifles or for personal purposes.

Barrack Obama’s attempted censorship of images proving Osama Bin Laden’s death provoked a powerful reaction in the U.S. The media demanded proof of Bin Laden’s slaying, apparently representing the public interest, or at least purporting to, and simultaneously suggesting and reinforcing the idea that any proof were needed. Is the head of any one man so significant that a government would deliberately deceive millions of people to bolster its own credibility? Perhaps U.S. citizens instinctively distrust their political paragons, although there is no clamour for proof when policy changes or spending cuts are politically justified to them.

The difference is violence, gore, action, vengeance, suffering. And this is the American cultural landscape. Bin Laden was public enemy number one, but the culture of hysteria and misunderstanding (or refusal to contemplate understanding) that has been cultivated in the U.S. makes every native Iraqi or Afghan a potential trophy; death is proof of the righteousness of U.S. neo-imperialism, and a cause for celebration.

Celebrating victory could be seen as a global culture: It is an opportunity to affirm the strengths of our tribe and our cause, to mock and belittle the defeated, and to do both with the reckless abandon that comes with the knowledge that, for now, the worst is over and our responsibilities are diminished. Under psychological duress in a conflict environment where there is no real victory, only political exclamation or mass extraction from the battlefield, the end of every fire-fight carries the weight of increased significance. This is indefinite war waged abroad by an invading force, it is not the protection of the homefront, or a legitimate cultural threat; it is justified by the knowledge that you are in a land which is ruled and lived in alike by non-people.

When violence becomes the measure of success for cultural superiority, it is no surprise that a phenomenon such as War Porn would be born. It is the grotesque fetish of murder, normalised by meaningless, endless conflict and the distorted notion of what victory is. It is symptomatic of the 21st century where there is no empathy for others and a kill is considered a trophy. The military is a violent community propelled by an oppositional ideology; with no real barometer of success or victory, no positive affirmation of their cause, allowing these images and videos have become the true spoils of war.

I write this blog with unequivocal condemnation, but also to pose a question: How could mainstream media report this deplorable culture without further desensitising its audience to violence and normalising the existence of such behaviour? Conversely, is it appropriate that such horrific truths are censored? Our media, like our military, are more tech-savvy than ever, and images of violence move units and make money, unless they directly harm the coffers of the media organisation.

Constructing copy around images may create a consumer atmosphere of the medium dominating the message; not for everybody, but many who scan the media don’t necessarily absorb, analyse and criticise. Especially online, news is a passive activity, and repulsive images are temporary; it is an easy choice to look away. but a choice nonetheless.

War porn is an issue that needs to be addressed on a governmental level, not widely condemned by prominent political figures when a grotesque image or video is leaked. Political manufacturing of the news agenda ensures that something so damaging to U.S. credibility is swiftly removed from the headlines at home. Global media ensures that those in occupied countries who may see the positive aspects of U.S. intervention quickly change their outlook, and perhaps even their attitudes toward violence. Propaganda has told us that the U.S. aim to win hearts and minds abroad but these actions demonstrate an absence of either to a sickening degree.

I cannot recommend strongly enough this article by David Swanson: It is shocking, but at the same time thoughtful and sensitive to its subject.